Prefácio para Cílios Prostíbulos

- Andréia Carvalho

- 14 de abr. de 2018

- 8 min de leitura

Atualizado: 15 de nov. de 2021

por Ana Cristina Joaquim

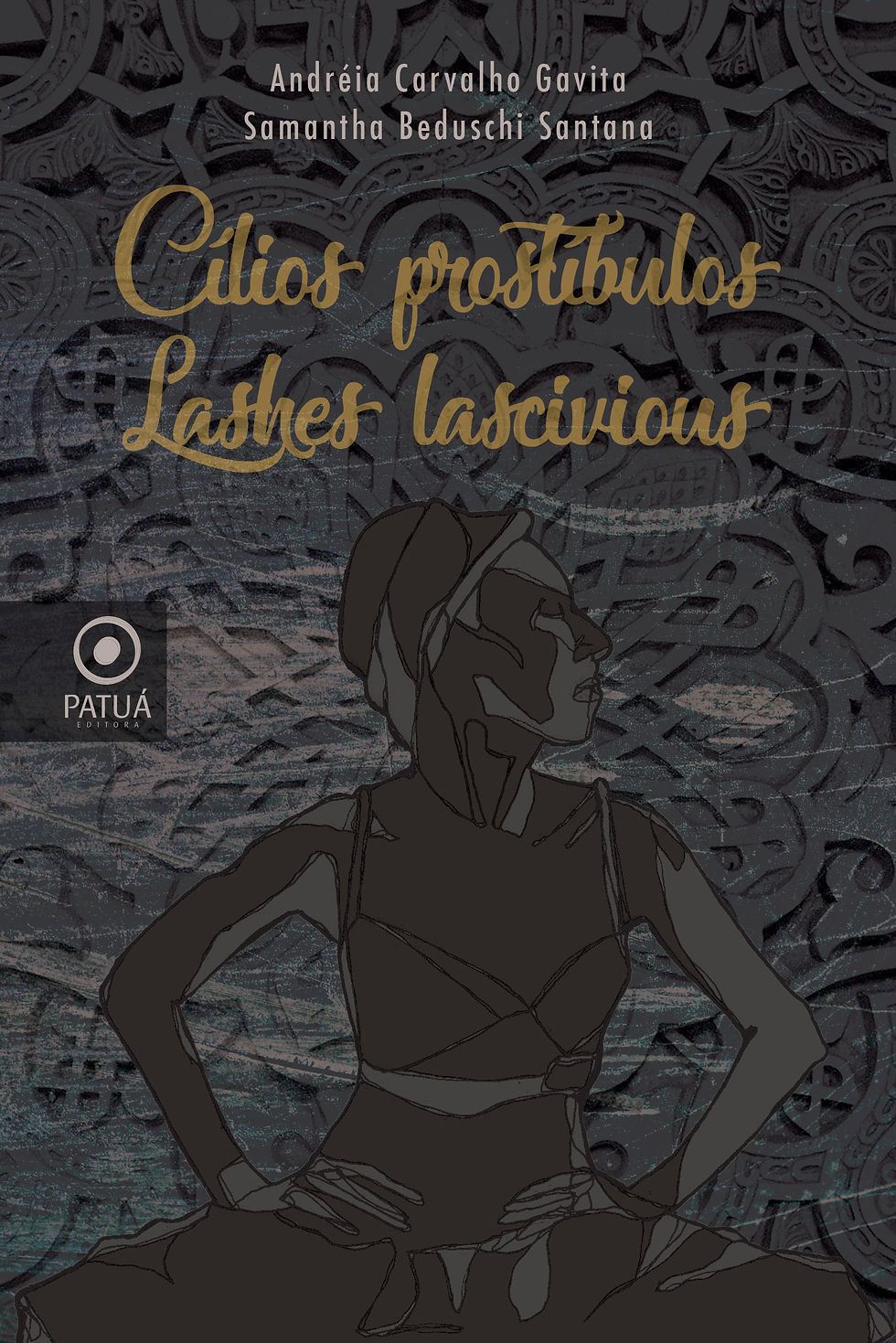

(Cílios Prostíbulos - Lashes Lascivious: Editora Patuá, 2018)

A mulher agencia a sua própria história. A mulher agencia a própria história. Assim é que discorro brevemente sobre o mais recente livro de poemas de Andréia Carvalho Gavita, Cílios Prostíbulos. Ou seja: é meu empenho centralizar, nesta nota de apresentação, o protagonismo da mulher para além de outras (e riquíssimas) formas de abordagem que esse conjunto de poemas me permitiria percorrer. Essa opção não se deve apenas à recorrência com que nos deparamos, leitores, com a figuração da mulher em ícones e símbolos das tradições ocidental e oriental (e o digo sem me furtar à percepção da relativa inutilidade, nesse contexto, inscrita na marca distintiva do binarismo oriente/ocidente), mas deve-se sobretudo a um fato inalienável, que vem subscrito na formulação anterior: o fato mesmo de que a mulher é um símbolo da tradição.

Para além de todos os esforços teóricos recentes com vista à elaboração de um discurso que deseja uma ultrapassagem dos papéis de gênero, Virginie Despentes afirma: “Possuo uma buceta no meio da cara” — obviamente não sem alguma ironia — e completa: “produzo mugidos vaginais”. A ironia não esconde, ao contrário, evidencia este dado de partida: ser mulher é ainda estar condicionada pela exigência de (des)obedecer a determinados papéis de gênero (o mesmo vale para homens… e o que dizer das derivas de atuação que travestis, transgêneros, homossexuais e bissexuais trouxeram em termos de complexificação no quesito biologia versus sexualidade ou no quesito biologia versus construção identitária?). A negativa destacada pelo prefixo entre parênteses muito tem a dizer acerca do embate que passa a ser, novamente — em termos de situação histórica presente —, um dos protagonistas das inquietações contemporâneas, e o ato de linguagem que possibilita à obediência se metamorfosear em desobediência é o cerne mesmo do resultado poético ofertado por Andréia Carvalho Gavita.

O que aqui se metamorfoseia é o próprio sentido dos termos que, colocados lado a lado, adquirem — quase por meio de uma operação mágica (faculdades obscuras de quem admite a linguagem como potência…) — poderes de vocábulos que os precedem ou os sucedem, como se contaminados nesse ato de bruxaria sintática e vocabular que transforma a “palavra” em palavra (contexto de dicionário transformado em contexto de intencionalidade). Cílios prostíbulos, diz o título; para pestanas que não se espantam com a pestilência, o subtítulo. Ora, colocar a peste à altura dos olhos já seria operação por si só dotada de grande impacto, mas Gavita vai além: contamina, com a delicadeza dos cílios fêmeos, o signo funesto que se metamorfoseia num processo vertiginoso de escrita (sim, contamina, pois a peste é contagiosa e se aloja em tudo que dela se acerca: a peste está imbuída de derivação prefixal – dado o apelo linguístico da pestilência…).

“A mola da atividade humana” — afirma Bataille em A literatura e o mal — “é geralmente o desejo de atingir o ponto mais afastado do domínio fúnebre (que o podre, o sujo, o impuro caracterizam): apagamos por toda a parte as marcas, os sinais, os símbolos da morte pelo preço de esforços incessantes”. Apagamos mesmo depois disto, se é possível, as marcas e os sinais desses esforços. Gavita, diversamente, não respeita afastamento de espécie alguma, mas promove aproximações impensáveis: os ingredientes que lança no caldeirão da escrita resultam em poções de feitiçaria mesmo, em que os reagentes (palavras) se modificam entre si, ao mesmo tempo em que modificam o gesto de recepção: o leitor não está imune a esta sorte de contaminação pelas sendas da magia.

Por meio de um percurso que dota a palavra de poderes transformadores, creio que a poeta responde à inquietação lançada por Silvia Federici em “Witch-Hunting, Past and Present, and the Fear of the Power of Women”: “How does one reconcile the all-powerful, almost mythical portrait that inquisitors and demonologists painted of their victims [women] — as creatures of hell, terrorists, man-eaters, servants of the devil?” Eu diria, conforme o impacto que a leitura dos poemas de Cílios prostíbulos me causou, que a reconciliação operada por Gavita — fruto, justamente, dessa aproximação por contaminação vocabular — opera com a reconfiguração do mal: conforme tradicionalmente entendido, força de que se deve afastar; conforme contextualizado na cena mágico-poética, força que inevitavelmente carrega o apelo da proximidade, e, uma vez nas vizinhanças, é metamorfoseado em signo de potência transformadora: “Trago a peste para dentro do corpo”, lê-se num dos versos, tão próxima a peste está do corpo, que com ele se mistura, permitindo assim que haja transformação mútua (da peste pelo corpo e do corpo pela peste). O signo mulher, portanto, escapa completamente às convenções dicotômicas, já que não seria mais possível pensá-lo como feixe de negatividades (tentação, desvio…) ou de positividades (delicadeza, amparo…), uma vez que as significações todas coexistem no caldeirão das operações metamórficas.

Inevitavelmente, aproximamo-nos delas: Afrodite (em composição: Afro-me-dite), Salomé, Nataraja — a beata cibernética —, a Esfinge, a Mandrágora afrodisíaca, Iara, Iansã, as Danaides, Melusina, a Amazona, e também as Gárgulas, em aviso constante de que o demônio não dorme nunca: há que se vigiar constantemente; e ainda Pandora, aquela que tudo dá, tudo tira e tudo possui. “A moça traça”, poeta que “Arrasta a corrente da voz pelo sótão da respiração”, a poeta Andrógino, que sobe os degraus com a laringe em chamas, a poeta Gavita (Gavita Rosa Gonçalves, costureira e poeta negra, esposa de Cruz e Sousa), “sendo aquela que tudo lê”, traz no peito “um coração ancestral” (pois as urgências dela são as urgências de todos os tempos: a afirmação da voz), é ela mesma um “trote de jade na veia de hades”: em metamorfoses diversas, não teme conduzir o ornamento à vida subterrânea, transita pelos espaços como um anjo caído a quem não tivesse sido vetada a subida aos céus, os caminhos entre as conotações do bem e do mal estão enfim abertos, e confundem-se.

“Poderiam dizer”, enfim “que se tratava de um sol satânico sobre os castos meridianos e que sua lucidez faiscaria efígies obscenas sobre as areias, incendiando casas santas”, e certamente teriam razão… “Mas ela, prometeica na fogueira da claridade, sustentaria o verbo com a lenta combustão de uma pluma migratória no acasalamento do deserto”.

A prostituta em tarefa hermética pratica comércios vocabulares, joga luz nos espaços obscurecidos: “E dela seria a voz, por tantas eras eclipsada”.

The woman crafts her own history. The woman crafts history itself. That is how I expatiate upon Andréia Carvalho Gavita’s most recent book of poetry, Lashes Lascivious. In other words, it is my commitment to focus on, in these introductory remarks, the prominence of women beyond other forms of approach which this collection of poems would allow me to cover. That path was chosen not only due to the recurrence of our — we, the readers — coming across with the women’s figuration in icons and symbols of western and eastern traditions (and this is I say with the perception of the relative uselessness, in this context, inscribed within the distinctive feature of the binarism of East and West), but most importantly due to an inalienable fact, which comes subscribed in the prior formulation: the same fact that the woman is a symbol of tradition.

Apart from all the recent theoretical efforts towards the creation of a discourse which looks forward to going beyond gender roles, Virginie Despentes states: “I have a pussy on my face” — obviously not without some irony — and continues: “I produce vaginal moos”. The irony is not hidden, on the contrary, it highlights this starting dadum: to be a woman is still to be conditioned by the demand of (dis)obeying certain gender roles (the same goes for men… and what to say about the drifts of actions which transvestites, transgender persons and bisexuals brought along in terms of complexifying the aspects biology versus sexuality or biology versus identity construction?). The negative highlighted by the prefix in parentheses has a lot to say about the clash that becomes, again — in terms of the present historic situation —, one of the protagonists of contemporary concerns, and the act of language that allows obedience to be metamorphosed into disobedience is the heart of the poetic outcome offered by Andréia Carvalho Gavita.

What transforms here is the own meaning of the terms that, placed side by side, acquire — almost through a magical operation (obscure faculties of who admits the language as potency…) — powers of words that precede them or succeed them, as if contaminated by this act of syntax and vocabulary witchcraft which transforms the “word” into word (context of dictionary transformed in context of intentionality). “Lashes Lascivious”, says the title; “for lashes which are not perplexed by pestilence”, the subtitle. Now placing the pestilence at the height of the eyes would already be an operation in itself endowed with great impact, but Gavita goes beyond: contaminating, with female eyelashes, the deadly sign that metamorphoses itself in a vertiginous writing process (yes, contaminating, because the pestilence is contagious and it lodges itself in everything around it: the pestilence is imbued with prefixal derivation — given the linguistic appeal of pestilence…)

“The spring of human activity” — states Bataille in Literature and Evil — “is usually the wish to reach the farthest point of the funeral domain (which the rotten, the dirty, the impure depict): we erase the marks all over, the signs, the symbols of death at the price of unceasing efforts”. We even erase after that, if possible, the traces and signs of those efforts. Gavita, diversely, does not respect distance of any kind, but fosters unthinkable approximations: the ingredients in the cauldron of writing come out as real potions of witchcraft, in which the reagents (words) interact and modify themselves, at the same time that they modify the action of reception: the reader is not immune to this chance of contamination through the trails of magic.

By means of a journey that provides the word with transforming powers, I believe the poet responds to the unrest awakened by Silvia Federici in “Witch-Hunting, Past and Present, and the Fear of the Power of Women”: “how does one reconcile the all-powerful, almost mythical portrait that inquisitors and demonologists painted of their victims [women] as creatures of hell, terrorists, man-eaters, servants of the devil?” I would say, according to the impact that the reading of the poetry in Lashes Lascivious had on me, that the reconciliation operated by Gavita — an oucome, indeed, of that approximation by vocabulary contamination — operates within the reconfiguration of evil: as traditionally understood, a force which one should keep away from; as contextualized in the magical-poetic scene, a force that inevitably carries the proximity appeal, and, once in the sorroundings, is metamorphosed into a sign of transforming potency: “I swallow the plague into the body”, it is read in one of the verses, the plague is so close to the body that it blends itself with it, thus allowing for mutual transformation (of the plague by the body and of the body by the plague). The sign woman, therefore, escapes dichotomous conventions entirely, since it would not be possible to visualize it as a beam of negativities (temptation, deviance…) or positivities (tenderness, support…), since all significations coexist in the cauldron of metamorphic operations.

Inevitably, we get close to them: Aphrodite, Salome, Nataraja — cybernetic blessed lady —, the Sphinx, the aphrodisiac Mandragora, Iara, Iansan, the Danaides, Melusina, the Amazon, and also the Gargoyles, a persistent warning that the devil never sleeps: constant watch must take place; and Pandora, the one who gives everything, takes everything and has everything. “The maiden moth”, poet who “drags the chain of voice through the attic of breathing”, the Androgynous poet who climbs “the steps with the larynx in flames”, Gavita (Gavita Rosa Gonçalves, an African descendant who was a seamstress and a poet, and Cruz e Sousa’s wife), “being the one that reads all things”, she carries in the chest “an ancient heart” (because her urges are the urges of all times: the assertion of voice), she is herself a “jade trot in hades’ vein”: in various metamorphoses, she does not fear to conduct such an ornament to underground life, moving through spaces like a fallen angel to whom the ascendance to heaven has not been denied, the paths between the connotations of good and evil are finally open, and blend themselves.

“It could be said that it was the matter of a satanic sun under the meridian chaste ones and that his lucidness would sparkle obscene effigies on the sands, burning down hallowed houses”, and they would be certainly right… “ But she, promethean in the fire of clarity, would sustain the verb within the slow combustion of a migratory plume in the mating of the desert”.

The prostitute at a hermetic task does vocabulary business, casts light on the obscured spaces: “ And hers would be the voice, for so many eras eclipsed”.

(Tradução de Samantha Beduschi Santana)

O livro, bilíngue, está disponível na loja virtual da Editora Patuá.

Comments